The Characters

Danny Murrow is the primary character in the work. According to the story, he wrote a memoire in 1939 recounting his life in the music of the twenties and thirties. It’s a coming-of-age story, but also a coming-to-be story, since Danny overcame a terrible deficit of childhood development. Abused and left to his own resources, an eight-year-old on the mean streets of the New York of the eighteen-eighties.

Danny Murrow is the primary character in the work. According to the story, he wrote a memoire in 1939 recounting his life in the music of the twenties and thirties. It’s a coming-of-age story, but also a coming-to-be story, since Danny overcame a terrible deficit of childhood development. Abused and left to his own resources, an eight-year-old on the mean streets of the New York of the eighteen-eighties.

He wrote:

As a child I didn’t have much of a chance to have a sense of who I was. I was, as they say, troubled. Who I am I owe largely to the woman who rescued me from the streets and volunteered to become the only mother I’ve ever known. She brought me into her little family and risked a great deal to give me what I have. I was to have a childhood after all, and a new start.

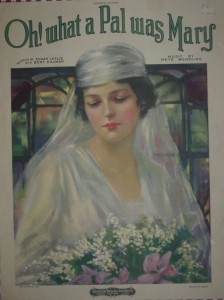

That childhood had a special grace always available to us in what most would say were difficult times. Mary was the source of transcendence, mostly through her Quaker heritage, but she really knew how to embrace the world too.

There were four of us in that little apartment. Mary and Jack and their natural son, Johnny. Jack, did his best to keep body and soul together for us all. He worked on the big press at the New York Post. He claimed that tuning up that old press was a lot like tuning the ancient piano that was the center of our musical world.

He could fix anything with his hands, but sometimes he couldn’t get them clean of the grease and ink before he came home exhausted. Still, he would sit down at the old upright, and play for a while. I thought every piano had those black and blue stains on the ivory keys. He’d bring a copy of the paper home every night, and we’d pour over it to learn to read and to see what was happening in the world.

Mary was the lady who looked in on so many struggling social programs in the city in those depression times of the eighties and nineties. She pulled me out of a desperate and brutal setting where my small life could have been lost in any number of ways. I believe she brought me out of a depressed state, a stuporous relationship with the world that was perhaps my only defense in a life so uninhabitable.

Her own son, Johnny, became my brother. Even though we are the same age, I was never a match for him in a fight. That was just about the first thing I found out about him, although if it hadn’t been my idea, I’m sure he never would have raised a hand to me. Always a quiet kid, more at peace than I, he spent so much time in his music, that he seemed somehow complete. We have had some wild times, though.

1888 a March blizzard filled the streets of New York with drifts of snow so high that people could not get from one block to another. The event cut deeply into the psyche of New Yorkers, and set the stage for bids to build the subway system – an expensive proposition that would probably have met with defeat if not for the blizzard.

We believe I was born in 1880. My father made only the one contribution to my existence. My mother doesn’t occupy any frame of conscious remembrance accessible to me. Passed through foster homes, I was finally handed down to a woman they called “Gama” but her besotted embrace was frightening and increasingly demoralizing, and I chose the streets as soon as I could get away.

Eventually caught stealing, I was introduced to the kind people of the social services. I would learn that my pastel captivity, as much as it was to be struggled against, would open out to something better. And that my prospects needn’t be limited to the menacing dark of some putrid crawlspace. The young captive I was could not help himself.

When Mary heard about my case, it wasn’t a good time for her. Her son Johnny was just eight years old as well, he was a splendid kid, all a mother could hope for, and she didn’t think Jack would be able to embrace what it might mean, to have another, a troubled child. It could represent a danger to the life they had. She was conflicted.

She once showed me an entry in her journal that described that time. She wrote that she thought at least she should see me. If she couldn’t take me, then maybe she could steer me to somebody, one of the charities, somebody who needed a sad case. “He was a mess, clingy and bristly at the same time; flighty and un-focused, probably terribly abused, what could anybody do?

The journal continued, “When Jack saw him, he seemed to recognize something. That was it, just that simple, he was ours. Before you knew it he had situated himself between the radiator and the piano and was curled up like a cat, and that was fine for the moment.”

There would come years of patient nurturing, hurt feelings, rage, piteousness, diffidence, small victories. “Jack seemed sufficiently happy just to see this little stranger rock with the piano, and later to hold the guitar like a hollow mace and allow himself to be drawn into the rhythmic pulse of the music. They had a dialog that words envied.”

“Jack could be a frightening physical presence, but there was something about the body language that meant they understood each other from the beginning. I was jealous of the simple man-to-man coexistence of two beings who had as much difference between them as I could imagine, yet shared something primal and plain. I saw in it the beginnings of the same conspiracy that Johnny and his dad enjoyed, and rejoiced in how far we had all come.”

Johnny was mystified, but not antagonistic. He didn’t seem to be protecting any territory, and that was a trait that Mary found satisfying. He did seem to have some of the un-carved block that the mystics had written about. There was no denying that he occupied that special place of firstborn son, but my probationary status eventually gave way to acceptance and finally membership in the only family I had ever had.

Johnny was quite advanced in his musical training at that young age, but there was a reluctance to play in his father’s presence. Mary was sure that Johnny was not afraid of competition with his dad, but perhaps was protecting Jack from some imagined injury in the obvious promise of his skills. That non-controversy said a lot about our little family.

He began to appreciate my struggle, and to align himself with it. Then it wasn’t that far to the Sunday comics, adventure games based on “The Count of Monte Cristo,” and other shared fantasies, and a deeper communication which seemed to flower most noticeably in the music. Playing offered a structure that didn’t depend on anyone’s authority, it was the harmonious dialog. One by one we found tunes we could play together, or at least in which my playing didn’t detract too much from Johnny’s genuine gift.

Soon it was a trio, Jack and Johnny taking turns at the piano, and Johnny on harmonica too. Eventually a little fiddle. I was holding very tightly to the fragile guitar, aching to fret cleanly, respectable intonation far in the future.

Mary was glad to look on and provide popcorn. Sometimes there were hilarious hijinks, and one time when the land lord appeared angrily at the door, fully prepared to have us thrown into the street for playing music. With just a little patient discussion, we found that we knew a lot of the same songs, and he went away humming a pretty good rendition of “Darktown Strutter’s Ball.”

In 1885, George Hearst had run for state senator in California, and to promote his candidacy, he had purchased the San Francisco Examiner. At the completion of the campaign, Hearst gave the newspaper to his son, William Randolph Hearst.

William, who had experience editing the Harvard Lampoon while at Harvard, brought three Lampoon staff members with him to California. One of the three was Ernest L. Thayer who wrote humor and signed the pen name Phin.

In the June 3, 1888 issue of The Examiner, Phin appeared as the author of the poem we know as “Casey at the Bat.” The poem received very little attention and a few weeks later it was partially republished in the New York Sun, although the author was now Anon.

Jack brought a copy of it home that summer, and everyone seemed to think it was very funny. I did too, eventually when I came to understand more of what it was about, and still cherish it as a glimpse of my limited awareness. It took a long time for me to understand that it was about a contest of baseball, something I had seen in the stickball street version, but never understood in terms of rules.

The language was immediately funny, words like “Mudville,” “Cooney,” “lulu,” and the image of “Flynn a-huggin’ third.” But frustratingly, so much of it was lost on me. It seemed like weeks before I could listen to it all the way through and understand it, and really a couple of years before I could read it to myself. I still get satisfaction from the last two stanzas:

“The sneer is gone from Casey’s lip, his teeth are clenched in hate;

He pounds with cruel violence his bat upon the plate.

And now the pitcher holds the ball, and now he lets it go,

And now the air is shattered by the force of Casey’s blow.

Oh, somewhere in this favored land the sun is shining bright;

The band is playing somewhere, and somewhere hearts are light,

And somewhere men are laughing, and somewhere children shout;

But there is no joy in Mudville – mighty Casey has struck out.”

I eventually did read. And read and read. I took refuge in one book after another, and that was joyful for Mary. She could send me into worlds created by loving genius in a thousand settings. Dickens, Dumas, Melville, Wolcott, Conan Doyle, eventually Scott and Clemens. She could even tolerate the Whiz Bangs and the Handy Books. Lots of things that she would never read, but didn’t mind seeing me read.